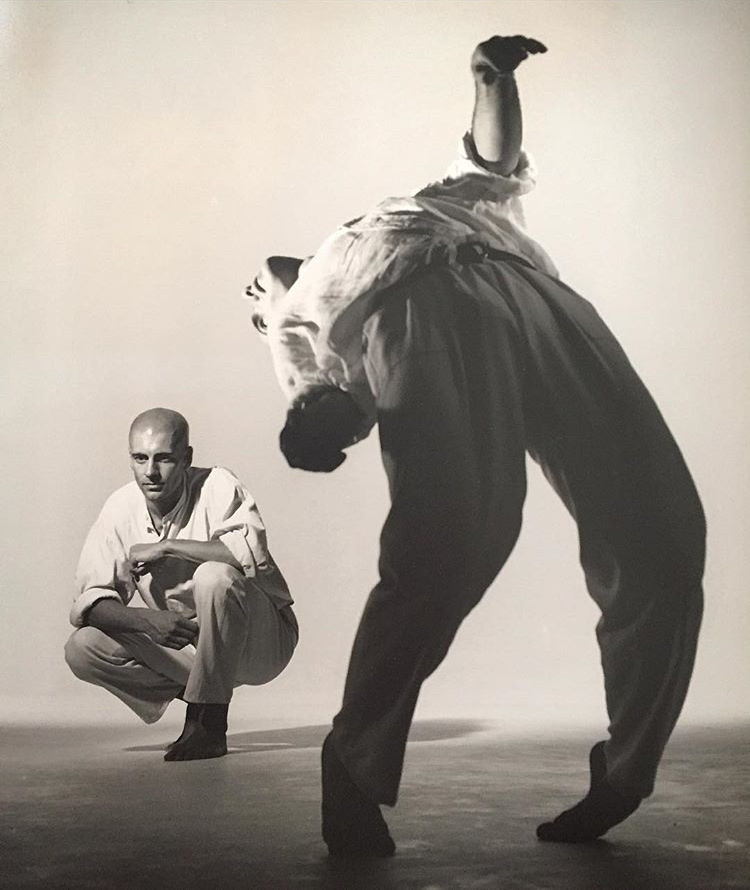

Assistant Director Fay Lomas takes us inside the second week of rehearsals for Alice Childress’ Trouble in Mind.

It’s been another action-packed week of rehearsals up in Notting Hill. We’ve been working through Act 2 and also spending some time going back over sections of Act 1.

As last week, upon approaching each scene, we spent a significant amount of time digging into the text, followed then by getting the scene up on its feet. We’ve been focussing on making sure we keep on adding in the detail. Everything has to be specific, nothing general. At times, this has meant asking ourselves – what’s the backstory to a line or a relationship? On other occasions, we did an exercise which involved the actors, on their line, pointing to the character(s) to whom the line is addressed. Linked to this, we’ve been asking which lines are private discussions between two characters, and which lines are intended for everyone to hear. With the private lines, we’ve asked ourselves, how do the characters achieve privacy within this rehearsal room? Where can they go to have a subtle chat? When lines are public we’ve also had to ask ourselves, how are the characters affected by what they hear? So, for instance, how do the other characters react to the director singling out one of the actors for public praise? The play is also full of interrupted conversations – Laurence has encouraged the actors to consider what a conversation would go on to say if it didn’t get stopped.

As last week, we’ve had to ensure that we don’t pre-empt rows. We’ve discovered that often characters are entering a discussion hoping it will go well, that they will be listened to, and then suddenly things spiral out of control. Connected to this has been the question, is there enough pressure on the characters to make them act the way they do? We’ve done a lot of work exploring how tension builds and what it is that makes an argument suddenly explode.

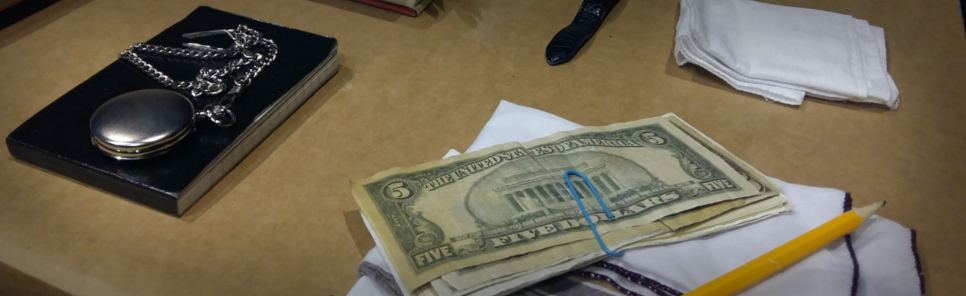

Besides detailed text work, there’s also been props galore. The smallest details in the script translate into things that take a lot of work in the rehearsal room. For instance, the play is set in the late autumn – this means that all the characters have coats, hats, scarves and gloves and the actors have to work out the precise choreography for taking them off when their characters enter the rehearsal room and for putting them back on when they leave. It sounds simple, but it’s amazing how complicated every day items can become when you’re onstage and trying to fit the action around what else is going on in the scene. And of course, the play within a play means that there are props and costume pieces associated with that too. Andrew Alexander, playing the stage manager character in Trouble in Mind, is kept very busy indeed moving ironing board here, bucket there, and scripts here there and everywhere!

This week, both in text work and in staging the scenes, we’ve rehearsed through dividing each scene in short sections, which we then rework many times, in lots of detail. Laurence encourages the actors to keep on asking themselves what worked last time and what didn’t and then to make new or different choices as they see fit. It’s amazing to watch how much detail and how many new discoveries emerge from this approach.

We’ve also been doing lots of work on the play within a play – which is a prominent part of Act Two. A challenge at the heart of Trouble in Mind is that the play is critical of the content of Chaos in Belleville (the play within a play) and yet quite a lot of stage time is dedicated to the actors rehearsing it – so it’s important that, on some level, the audience is invested in the story of Chaos in Belleville and the characters and relationships within it.

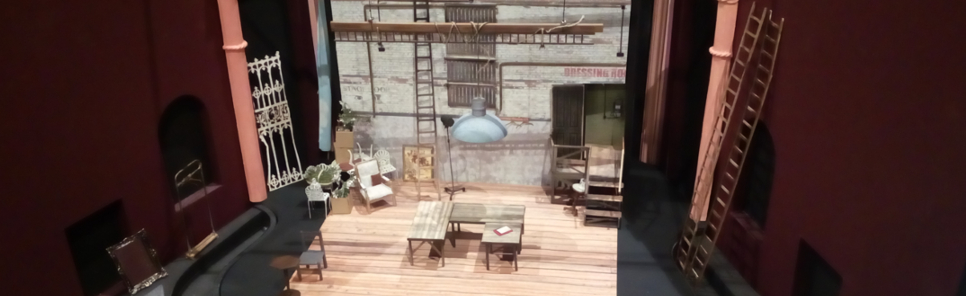

This week also saw lots of costume fittings, and the get in: so our set is now basically up in the theatre.

We’re heading excitedly into our final week of rehearsals in the rehearsal room now, before going into tech the following week.

Trouble in Mind | 14 Sep – 14 Oct | Book Now