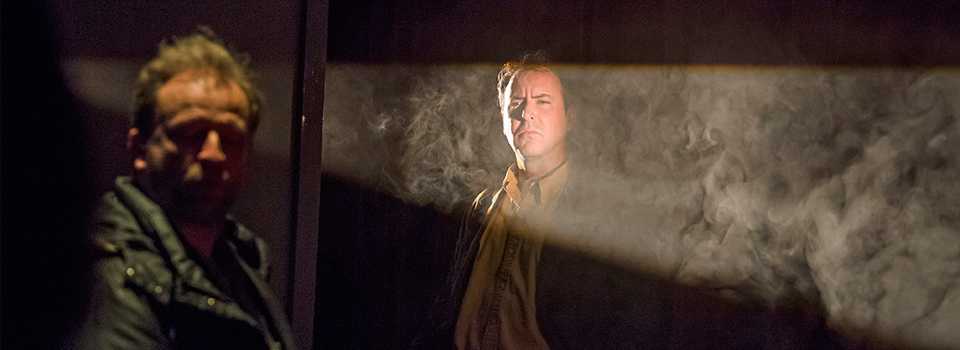

Photo by Tristram Kenton

Your plays are often named in connection with the work of Strindberg and Bergman, as works which take us to the dark heart of social existence.

Yes, well, Strindberg was mad. It was a kind of controlled madness which he used as a tool. He was very skilful at that. My roots are also in English-language theatre, specifically in the plays of Beckett and Pinter. We started putting on Pinter very early on in Sweden. Pinter taught me about communication. People often say we should communicate more, but he thought that we did it too much, that by capturing too much of ourselves and others in language, we easily imprison ourselves and end up using language to hide something we too carelessly revealed.

One of the things your plays share with Pinter and Beckett is that your plays have a distinctly musical quality. The play of lines – between characters who are given no more background detail than is needed to allow the play to work – has a distinctly contrapuntal quality.

I hate stories. I can’t even read stories any more. Whenever I see a story developing I stop and go back. What fascinates me is the material and stories get in the way of that. I want to look at this point when you can feel the material coming alive so that it brings with it a way of seeing. I’m interested in individual moments, pictures or fragments.

When I direct I talk about the scenery as music, but I never now use actual music in my plays. What fascinates me is composing structures which work on different levels. I can start with a phrase which keeps coming back. It might contain nothing to begin with, but as the play of levels progresses it will suddenly fill out, bringing a whole world into view.

Theatre creates a kind of way of looking, a resonance. What interests me is the moment of indeterminacy which blooms in the gap between what is said and what is answered.

Tell us a little about how you write.

When I start to write I am like a bird who is about to leave for Africa. The birds gather, swallows. They wait and watch for days and days until the right moment. When they see it, they go. I have been writing since I was 15. My words give themselves to me more readily every day. At the same time, the nearer one comes to capturing something in language, the more visible becomes the gap between the described and the description. It’s a failure, but a failure which can still take you closer to something in a different way. Words create a shadow. Those are real.

Your plays often confront strong social issues, such as terrorism, as well as more general issues to do with characters breaking down on discovering something about themselves.

I am less and less interested in what happens in the world. At 74 years old it’s a world I am preparing to leave. I write most now about older people, not because I am old myself but certain details – the colour of a toy, the feeling of evading a caress – are more luminous to one who looks back more than they look forwards.

But do the realities of life, in modern Sweden say, have a relevance?

Certainly, the false harmoniousness of Swedish life lends a certain explosive power. Sweden is a successful country. Our social reforms sit very deep. But like elsewhere, our politicians have failed us. We say we are a country that hasn’t been at war for 200 years, but in Sweden live many thousands of people who come from wars. Those wars live on in them. They become our wars. You can’t contain these conflicts by keeping them hidden under the illusion of harmony. The big explosion hasn’t yet come here.

Is language a part of this?

Yes. Swedes have learnt very well the game of disguising what they think. One avoids subjects. One is afraid to say anything inappropriate in company. It’s like we are afraid of the world. I have become more and more disgusted with this conformity. Language is thinning out under the pressure of conformity. We hide increasingly behind euphemisms which leave a kind of mucus over everything we talk about. The truth comes out when people are drunk. Or when someone is about to die. It’s a special kind of truth.

Your plays often focus on explosive points, though the surface of the plays is often very calm. Do you think theatre can also help us?

The empty stage is sacred to me. It’s the place of our greatest ambitions and for our hardest truth-seeking. An audience absorbs the best and the worst moments of life. You don’t need to identify with characters. You take what you see and carry it away with you, inside.

With film, even though it has perfected in many ways the art of illusion, one is still constantly aware of the medium. But with theatre, when done well, can be entirely transparent.

Is the theatre itself in danger?

Theatre has existed for over two thousand years, maybe much more. It shows no sign of going under. But it does betray itself. There are too many special effects, too many celebrities looking to sell themselves, or to be loved, to become their children, cradled in the loving gaze of the audience.

Theatre must return to the word and the naked stage. Because there is nothing more beautiful than an actor on the stage, an actor plainly, really there. That’s truth. Everything else just gets in the way.

Interview by Guy Dammann

Act and Terminal 3 | 1 – 30 June | Book Now